Friends & Families of Syria’s Disappeared Develop a Roadmap for Justice

Kristyan Benedict - @KreaseChan

In the autumn of 2019, Syrian survivors of torture and familes of those still missing, gathered in rural Holland to work on what would become, nearly 18 months later, the Truth and Justice Charter.

I spoke with one of its main architects, and longtime Amnesty partner, Ahmad Helmi who runs the Ta’afi initiative. He described the aims of the charter, what he wants to see happen with it, and his current disappointment with the UN Syria Envoy and the slow progress his office has made regarding the well-being of detainees.

What is the Truth & Justice Charter?

The charter is a common vision for victims and survivirs of torture, and families of the forcibly disappeared groups to establish a road map for the future of justice and accountability in Syria. It helps us answer a key question - “what is the form of justice we, as survivors and victims, want for Syria?”

The charter sets out the demands and visions of the victims in a clear and concise way; so it is accessible to everyone, and so anyone with a desire to strive for a victims’ centered justice is aware of the victims’ priorities and demands.

How did you create it?

The five victims’ groups had a common desire to go beyond slogans. It is an attempt to offer answers and suggest solutions for questions and challenges we are facing within the Syrian context.

The idea started in 2019, when Syrian victims’ groups started working more closely together. We started to feel the harmony and complementarity of demands we had when coordinating before advocacy meetings.

This made us think, why don’t we create a document that has our shared vision, priorities, and demands. So we started working together to draft the charter. The first meeting was held in the Netherlands in the presence of advocacy experts, justice experts from contexts other than the Syrian one, and experts in transitional justice who offered their professional insights. We started brainstorming, arguing, disputing for a long while until we finally got to a form that we all agreed on. Nearly 18 months later, with countless meetings, consultations, and arguments, we got to this final form of the charter, characterized by a short- and long-term vision, the urgent procedures and steps that should take place right now, and the less urgent procedures that should take place in the future.

Who do you want to read it?

The charter is primarily addressed to victims, families of the disappeared and survivors of detention to offer an ethical commitment from us as victims’ groups and civil society organizations willing to adopt this charter, to say that we will not abandon any of these demands. We also want the wider Syrian civil society to read it and adopt it to be the common ground rule for a large number of voices and Syrians.

The charter is also addressed to all stakeholders in the justice and accountability field such as Syrian civil society organizations and international organizations who are striving for justice in Syria. We want them all to adopt a victims’ centered approach to justice and the wider crisis. With this charter, we offer that victims’ centered vision of justice.

We also want this charter to get to key decision-makers, states that are actively involved in Syria, for them to know that Syrian victims have practical recommendations and are not an obstacle in the face of justice. We want them to adopt this vision and orient their efforts toward it and to centering victims in their dealings with Syria.

Have you sent the charter to key UN diplomats and state representatives (Russia etc) - if so, what has been their reaction?

We sent it to all the relevant UN agencies, contacts at the human rights council, state representatives, representatives of foreign ministries of states that are actively involved in Syria. We did not share it with anyone from the Russian side, but we are planning to. The feedback of the recipients varied. For instance, the IIIM was very motivated and welcoming of the charter, and they said that they will support this vision. The same thing goes for the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Enforced Disappearance and many states. They welcomed and supported the charter - we will be following up with all of them so the demands can be implemented.

Can you tell us if anyone from the UN is helping you to operationalize the document?

No one from the UN helped us to operationalize the document, we are the ones who set the executive action plan and the future practical steps as victims’ groups, with consultations from different experts. Our next step is to publish a report suggesting an international mechanism to reveal the fate of the disappeared. This effort is supported by Jeremey Sarkin, a former member of The Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances. We will always strive to be the ones suggesting solutions so that they have legitimacy from the Syrian community.

Do you plan on getting the charter circulated inside Syria, including in regime-held territory?

We want the charter to reach regime-held areas, hence we tried to get to media outlets that are popular inside Syria to pick up the story. We are developing a special plan to deliver the charter by other means to people inside Syria.

The charter calls for a special international criminal tribunal for Syria as an option for justice & accountability. What progress has there been on this track?

When we talk about accountability at international courts, unfortunately, we see no real progress in this field, and it seems that there will be no progress. The only progress is perceived to be preparatory for this step in the future, such as the work of the IIIM, which is preparing files and dossiers, so that one day when trials can take place, the prerequisites are ready. However, the presence of courts based on the universal jurisdiction mandate is contributing to change the political environment and consequently increase the chances of putting those who committed war crimes in Syria on trial. We hope to see more states doing what Germany has done.

The UN Syria Envoy says the file of detainees, abductees, and missing persons is one of his key priorities – has that been your impression? What more must he do to see real progress on these issues?

To be honest, this was said by Geir Pederson the first time we met him in 2019 when he was first assigned as the UN’s Special Envoy to Syria. He said that detention and enforced disappearance is one of his first file priorities, but unfortunately, we did not see this in practice.

Until now, there is no real progress on the file of detainees and enforced disappearance in Syria despite COVID 19, which led many totalitarian regimes including Iran, to release a large number of detainees. In Syria, this did not happen. The lobbying that Pederson exerted was not enough to lead to the release of detainees, or at least to enhance the detention conditions.

Also, the Astana track is totally paralyzed with no progress whatsoever. We consider it an unhealthy track for Syria because it revolves around exchanging detainees, which we are against because Syrian detainees were detained based on their expression of opinion and are not war detainees.

What should have happened? Pederson should have lobbied and pushed the Syrian regime and its allies further, and not allowed the work on the constitutional committee to move on before reaching real progress on the detainees’ file. The constitutional committee’s presence is now an excuse for many countries including Russia to say that a political solution is underway but in reality, it is a waste of time and an act of stalling.

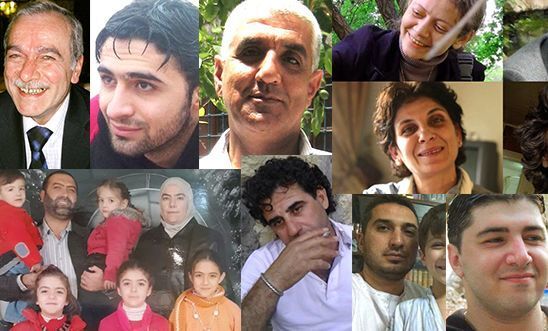

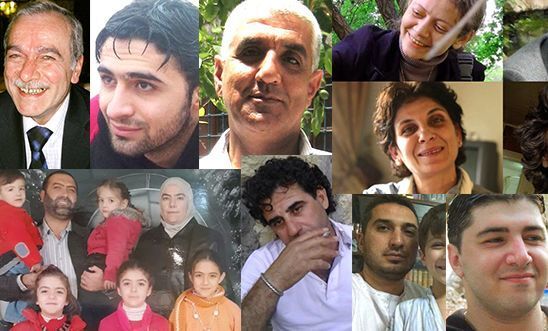

The founding signatories of the Charter are:

Our blogs are written by Amnesty International staff, volunteers and other interested individuals, to encourage debate around human rights issues. They do not necessarily represent the views of Amnesty International.

0 comments