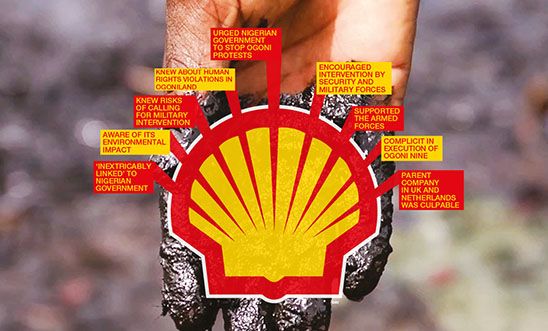

Shell: A criminal enterprise?

In the 1990s, the Nigerian government carried out a horrific crackdown on protesters against pollution caused by oil giant Shell in the Ogoniland region. It culminated in the execution of writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other men, known collectively as the Ogoni Nine.

Two decades on, we have conducted a ground-breaking review of thousands of pages of internal Shell documents, government reports, witness statements, archival material and other evidence. Together they point to the Anglo-Dutch company’s complicity in murder, rape and torture committed by the Nigerian government.

Shell and the Nigerian government were ‘inextricably linked’

In the 1990s, Shell was the most important company in Nigeria. The company and the government were business partners in a joint venture and remained in constant contact. As Brian Anderson, chair of Shell Nigeria between 1994 and 1997, acknowledged: ‘The government and the oil industry are inextricably entangled.’

Shell was aware of its environmental impact

Although Shell publicly denied its operations had caused environmental problems, senior staff were highly concerned about the poor state of its ageing, inadequately maintained and leaky pipelines. In November 1994, Shell Nigeria’s head of environmental studies, Bopp Van Dessel, resigned, stating that he felt unable to defend the company’s environmental record ‘without losing his personal integrity’. In a 1996 TV interview, he said: ‘Shell managers were not meeting their own standards; they were not meeting international standards. Any Shell site that I saw was polluted... It was clear to me that Shell was devastating the area.’

There is irrefutable evidence that Shell knew the Nigerian security forces committed grave violations when they were deployed to address community protests

Shell knew the risks of calling for military intervention

There is irrefutable evidence that Shell knew the Nigerian security forces committed grave violations when they were deployed to address community protests. In 1990, it called for a paramilitary police unit to deal with peaceful protesters at Umuechem village. According to an official enquiry, the police descended ‘like an invading army that had vowed to take the last drop of the enemy’s blood’, killing 80 people.

Shell knew about human rights violations in Ogoniland

From mid-1993, as violence increased in Ogoniland, it is inconceivable that Shell was not aware of the worsening human rights situation. The involvement of the armed forces was widely reported at the time, and Amnesty and others published numerous materials on incidents such as the detention of Ken Saro-Wiwa and extrajudicial killings of Ogoni residents. Shell executives regularly met with top government officials and discussed the government’s strategy for dealing with the Ogoni protests. The company also had close links with Nigeria’s internal security agency: Shell’s former head of security for the region said he shared information with the agency on a daily basis.

Shell urged the government to stop the Ogoni protests

Shell executives repeatedly underlined to government officials the economic impact of the Ogoni protests and urged them to resolve the ‘problem’. For example, on 19 March 1993, Shell wrote to the governor of Rivers State requesting his ‘intervention to enable us to carry out our operations given the strategic nature of our business to the economy of the nation.’

After General Sani Abacha seized power in November 1993, Shell wrote almost immediately to the newly appointed military administrator of Rivers State saying that ‘community disturbances, blockade and sabotage’ had led to a major drop in production and asked for help to ‘minimize the disruptions’.

Shell encouraged intervention by security and military forces

Despite knowing serious human rights violations were almost inevitable, Shell asked for the intervention of the Nigerian security and military forces. In 1993, for example, it repeatedly called on the Nigerian government to deploy the army in Ogoniland to prevent protests from disrupting the laying of the pipeline. As a result, 11 people were injured and one man was killed. Shell executives even advised the Nigerian military not to release protesters without commitments to stop protests.

Shell provided logistical support to the armed forces

Shell provided the security forces with logistical support and payments during the 1990s, with Brian Anderson admitting this was standard practice: ‘In reality, any operational contact with the government requires financial and logistical support from Shell. For example, to get representatives of the Department of Petroleum Resources to view an oil spill we often have to provide transport and other amenities. The same applies to military protection.’

Shell was complicit in the execution of the Ogoni Nine

Shell recklessly encouraged the military authorities to stop protests by the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), even after the authorities repeatedly committed human rights violations in Ogoniland and specifically targeted Ken Saro-Wiwa and the movement. Even after the men were jailed, being subjected to torture and other ill-treatement and facing the likelihood of execution, Shell continued to discuss ways to deal with the ‘Ogoni problem’ with the government, and did not express any concern over the prisoners’ fate. Shell later claimed it worked behind the scenes to advocate for the release of the Ogoni Nine, but we have seen no evidence of this. Indeed, one month after the executions, President General Sani Abacha complimented Shell on its stance.

Despite knowing serious human rights violations were almost inevitable, Shell asked for the intervention of the Nigerian security and military forces

Shell’s parent company in the UK and the Netherlands was culpable

Company documents show that, at least from the time that Shell appointed British national Brian Anderson to head its Nigeria operations in early 1994, key strategic decisions were taken in the corporate headquarters of Royal Dutch/ Shell in London and The Hague.

These include the regular ‘Nigeria Updates’ Brian Anderson sent to his superiors. They demonstrate that Shell directors in The Hague and London were fully aware of what was happening in Nigeria, with a clear directing role evident.

What is Amnesty calling for?

An individual or company can be held criminally responsible if they encourage, enable, exacerbate or facilitate a crime, even if they were not direct actors. For example, knowledge of the risks that corporate conduct could contribute to a crime, or a close connection to the perpetrators, could lead to criminal liability. Bringing the massive cache of evidence together is a key step in bringing Shell to justice. We will now be preparing a criminal file to submit to the relevant authorities, with a view to prosecution.

Decoding the oil spills

The Niger Delta is one of the most polluted places on earth, and every year hundreds of oil spills further damage the environment and devastate communities. Oil companies like Shell often make false claims about spills to avoid paying adequate compensation or properly clearing up their pollution.

There is a vast amount of publicly available data on spills in the region dating back to 2011. But it is too much for our researchers to analyse alone, so in 2017 we turned to our network of ‘digital decoders’, volunteers who use their phones and computers to sift through the data and verify the causes, locations and images of oil spills. In total, over 3,500 people from 142 countries sorted through nearly 3,000 images and documents.

Our researchers are now analysing the results and looking for evidence to hold oil companies to account.