USA: Mississippi Set to Execute 79-year-old Man

At the trial, retrial, and re-sentencing of Richard Jordan, the same prosecutor led for the state throughout – as an Assistant District Attorney at first and later recalled from private practice to act as a special prosecutor at the request of the victim’s family. Richard Jordan was first brought to trial in 1976, convicted of capital murder and automatically sentenced to death. After the capital statute was ruled unconstitutional, he was re-tried in 1977, with the same outcome. In 1982, his death sentence was overturned due to an improper jury instruction. In 1983, he was sentenced to death for a third time. This was vacated due to the improper exclusion of mitigation evidence. At this point, the prosecutor offered Richard Jordan a plea deal whereby he would receive life without parole (LWOP) in return for agreeing not to appeal that sentence. The prosecutor listed reasons to support the deal, including Richard Jordan’s remorse, his good conduct during 15 years in prison, his attempts to make “significant contributions to society”, his “positive force” in prison, and his military service during the Vietnam War. The trial court accepted the plea deal. However, this 1991 deal proved to be invalid because at the time it was entered, LWOP was only applicable to individuals found to be habitual offenders, unlike Richard Jordan. When (in another case years later), this error was revealed, Richard Jordan sought to have it corrected in his case via a reduction of his LWOP sentence to life imprisonment. The state Supreme Court vacated his LWOP sentence but said that the state could seek the death penalty at a resentencing if it so chose.

In 1985, the US Supreme Court established that states must provide indigent criminal defendants whose mental health would be an issue at trial with access to a mental health expert sufficiently available to the defence and independent from the prosecution to effectively “assist in evaluation, preparation, and presentation of the defense”. Prior to the 1998 resentencing, Richard Jordan’s lawyers moved for a psychiatric assessment of him to determine whether he had combat-related PTSD from his time in Vietnam. The court responded by appointing a state-employed psychiatrist not experienced in combat-related PTSD and the judge ordered that his subsequent report be provided to both prosecution and defence simultaneously. The report, based on a two-hour interview, concluded that there was no evidence of PTSD, instead concluding that he had antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), a prejudicial finding and since shown to be a misdiagnosis. Richard Jordan’s accurate report that he had been honourably discharged from the Army was dismissed as a lie and the assumption that he been dishonourably discharged was used to support the ASPD diagnosis. The defence opted not to call certain witnesses for fear that they would be undermined by the prosecution using the psychiatrist’s report (as occurred with their first witness).

With nothing in the record to suggest that the factors he had listed in 1991 as supporting a life sentence had changed, the prosecutor argued that life for the defendant was not justice, that his “trusty” status (earned for good conduct while serving LWOP, and which gave him some limited freedom of movement in the prison), gave him “absolute freedom” to “stroll around”, and have outside contact by phone, while the victim’s family “suffer more than he does” in a kind of “reverse punishment”. It would be “a death [knell] for our criminal justice system”, he said, “to allow this charade to continue”. He “is enjoying the good life” and “killing society today”. These and other inflammatory arguments breached international standards requiring prosecutors to “perform their duties fairly” and “respect and protect human dignity and uphold human rights”. Under human rights treaty law, signed by the USA in 1977 and ratified in 1992, “the essential aim” for the treatment of prisoners is “their reformation and social rehabilitation”. Using evidence of rehabilitation and a good prison record to argue for a person’s execution flouted this principle.

The appeal lawyers argued that the 1998 death sentence resulted from unconstitutional prosecutorial vindictiveness (retaliation against a defendant for exercising a legal right – here, Richard Jordan’s motion to have his LWOP sentence reduced to life imprisonment after the invalidity of the plea deal came to light). In 2014, the US Court of Appeals refused to allow the claim to proceed, over a dissent from one of the three judges. The latter found there was a “good claim” pointing to prosecutorial vindictiveness, noting that two other capital defendants, convicted of equally heinous crimes, and whose plea deals were vacated for the same reason, had received life sentences. The difference, the federal judge added, was that they had different prosecutors. This discrepancy, unexplained by the state, was “troubling”, he wrote, and the vindictiveness claim had sufficient merit to warrant a full hearing. Even the two judges in the majority noted that in a sister Circuit, the Court of Appeals had granted relief to an Arizona capital defendant with a claim of vindictiveness largely identical to Richard Jordan’s. When the US Supreme Court declined to intervene in the Jordan case in 2015, three Justices dissented, arguing that the requisite threshold showing that “his constitutional rights were violated” had been made and that the full merits of his claim should be heard.

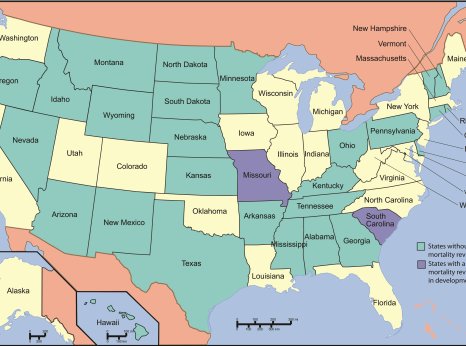

There have been 1,629 executions since 1976, when the US Supreme Court upheld new capital statutes. All these have been carried out since Richard Jordan was first sentenced to death. Mississippi accounts for 23 executions, the last of which was conducted on 14 December 2022. There have been 22 executions in the USA in 2025. Amnesty International opposes the death penalty in all cases unconditionally.