Justin Wong: Uncensored

You can read the original Traditional Chinese version of this interview HERE.

Justin Wong, a prominent political cartoonist and former Assistant Professor of Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University, has taught comics and worked in the field for over ten years.

Since 2006, he published a daily political cartoon column in the local newspaper Ming Pao, with his illustrations also featured regularly in the paper’s Sunday supplement.

After the enactment of the National Security Law, Wong’s political artwork satirising the police and officials has been challenged by Hong Kong authorities and their mouthpieces.

In December 2021, one year after the enactment of the National Security Law, Wong left Hong Kong for the UK. His departure followed a suspicious internal complaint made to university management concerning one of his Ming Pao articles, prompting him to leave in haste.

Translated Interview in English:

Hong Kong political cartoonist Justin Wong: suppression, self-censorship and persistence to keep the flame of democracy alive

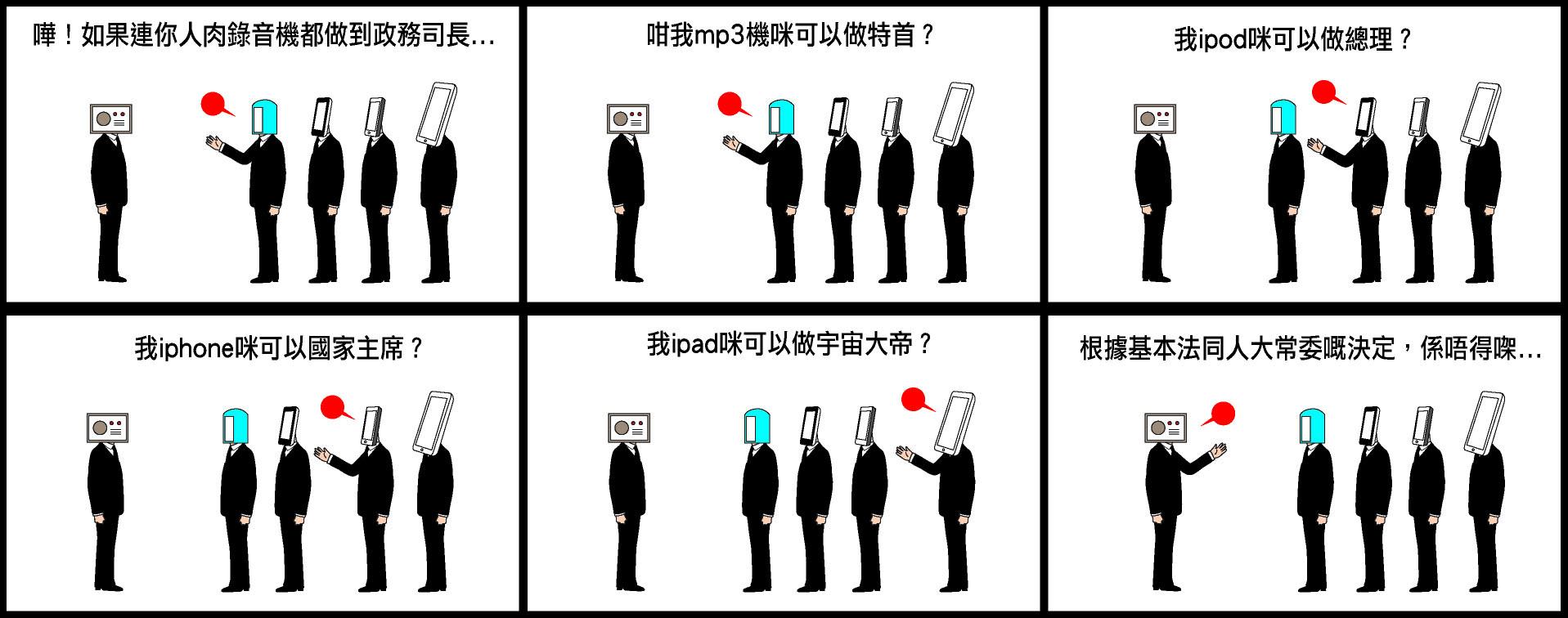

Justin Wong, a former assistant professor at the Academy of Visual Arts of Hong Kong Baptist University, began drawing political cartoons in 2007 for Ming Pao, a prominent local paper. His column, originally titled Giggling Squeaks, focused on political issues. Even after the Hong Kong National Security Law came into effect in 2020, he didn’t stop drawing. It was not until September 2021 when one of his cartoons was criticised by the Hong Kong police as “baseless and defamatory”. He felt he had no choice but to end his 14-year-long column. Although he said Ming Pao didn’t put any pressure on him to close the column, he still decided to do so due to the stress and his concerns for his family.

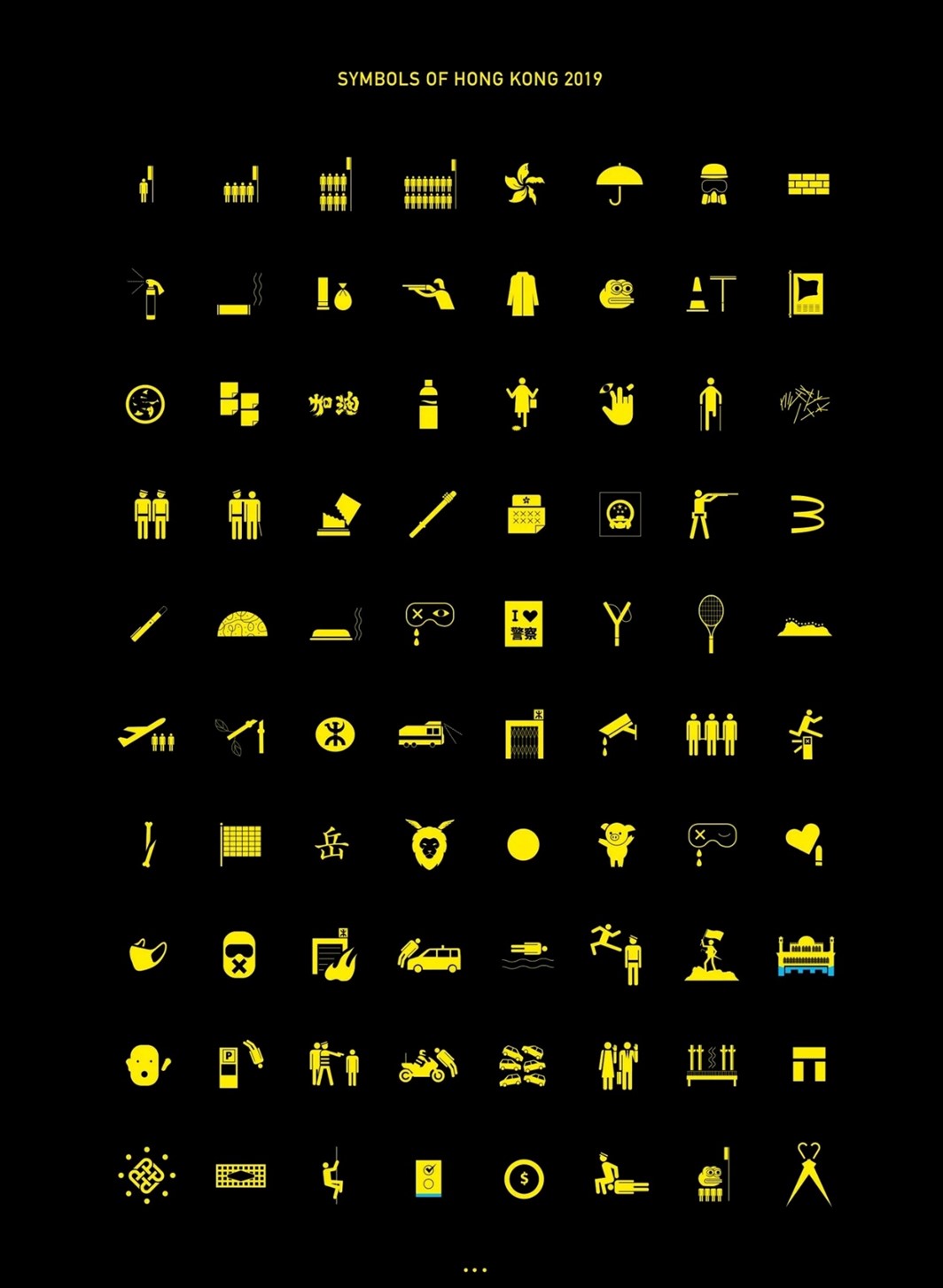

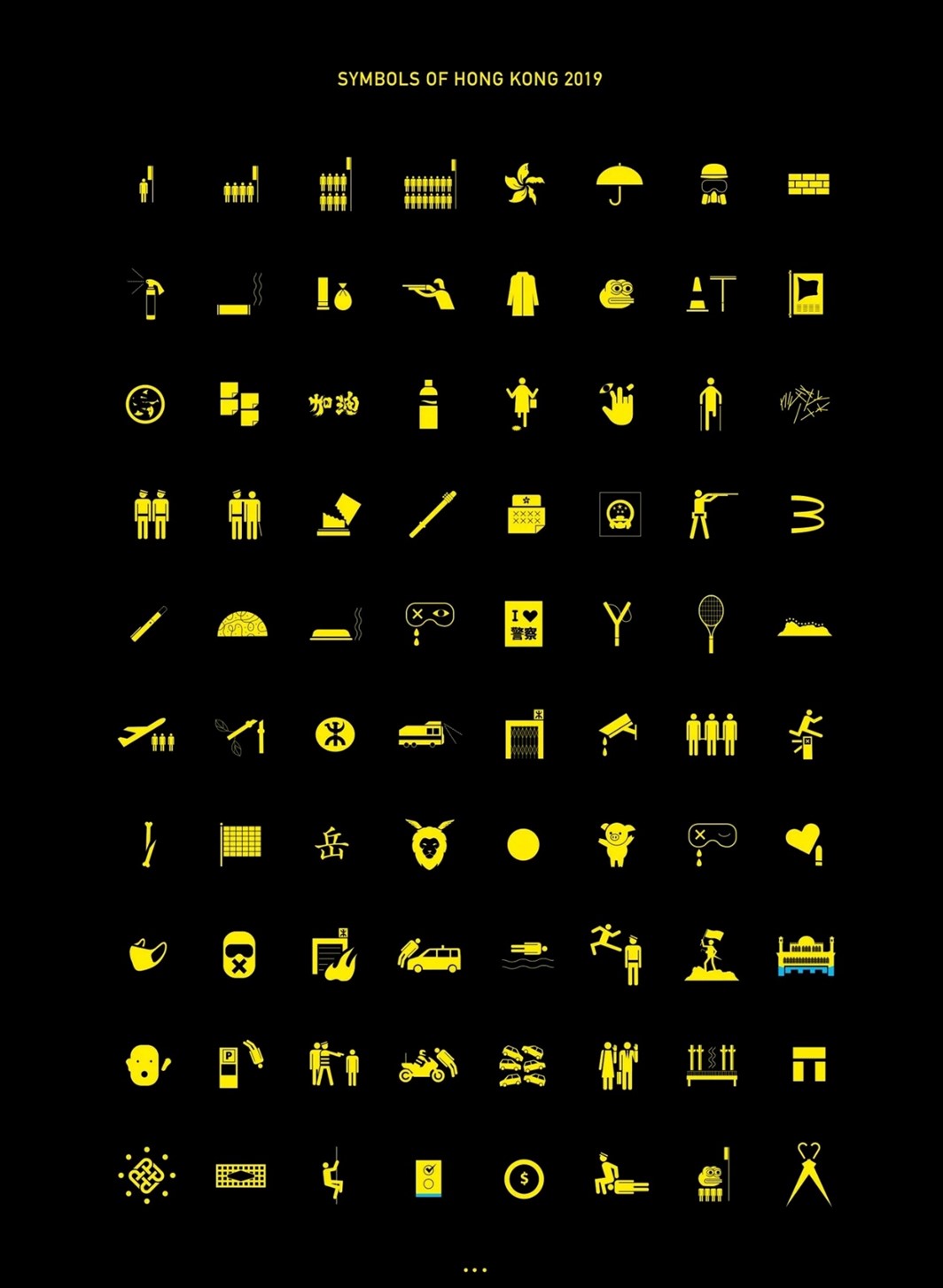

From the moment Justin was accused by the Hong Kong police, he was put under intense political pressure. As a scholar in visual arts, he once published a short academic paper of a few hundred words to analyse the imagery and symbols used in the Hong Kong 2019-2020 anti-extradition law protests. Shockingly, he was reported to the police by senior management at his university as a result. This became the final straw that pushed him to leave Hong Kong.

But even after resettling in the UK, he felt lost. Worried about his family’s safety, he is still constantly self-censored in his creative process.

Political awakening on 1 July 2003

Justin’s collaboration with Ming Pao initially began in the publications education section, drawing children’s comics. “I started drawing political cartoons because of the political awakening on 1 July 2003. At the time, hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers took to the streets to protest Article 23, a homegrown legislation that would criminalise “threats of national security”.1 “A lot had happened, but I couldn’t participate,” he said. Justin was studying for a Master’s degree in the UK at the time. When he returned to Hong Kong after graduation, he drew a political cartoon for Ming Pao. “Different from traditional political cartoons, my drawing style is more subtle. They liked it very much as it suited the style of the newspaper.” From then on, he started his column in Ming Pao and became known as a political cartoonist.

“I felt like I could express and share my views or dissatisfaction about society. The government could also understand public opinion through political cartoons.” Justin believes that the power of political cartoons lies in their ability to resonate with readers. Even without the power to hold the government accountable, cartoons can still reflect the thoughts of the majority.

Freedom of Creation before the National Security Law

Justin officially began as a political cartoonist for Ming Pao in 2007. He recalls that the creative atmosphere then was quite free, “When Donald Tsang was the Chief Executive, there was the least pressure. The Chinese government had not yet shown deep control over Hong Kong, and people still had hope for universal suffrage for the Chief Executive. I wasn’t a political figure and didn’t understand politics, yet I could participate. As an artist, it was my happiest time with the most significant growth in my creativity.” He added that everyone understood where the “bottom line” was; as long as you stayed within it, you were safe. “If you were a pan-democratic supporter, or part of a certain camp, you’d know the red lines of the opposite side. These boundaries were shaped by political ecology, and the government did not limit what you could say.”

In his view, the government did not intend to restrict freedom of expression or creativity at the time. His own “red line” was China-related news, which he avoided simply because he did not know enough, not because of any top-down prohibition. Ironically, if he were to take out his old works now, they would likely all be banned.

The red flag from five stars to one

Justin first felt the real presence of a “red line” when the National Flag Ordinance and Regional Flag Ordinance were introduced. “I used to draw the Chinese Five-Star Red Flag and the Hong Kong Regional Flag often. It was the easiest way to represent China and Hong Kong. But after the Ordinance was passed, I didn’t dare draw the Five-star Flag anymore. I changed from five stars to just one.” Though the law did not explicitly ban drawing the flag, it prohibits any act of desecrating the flag, but what counted as “acts of desecration” was vague and was defined by the authorities.

He also recalled that during Ming Pao’s 50th anniversary in 2018, he submitted an illustration that included the national flag. However, the editor advised against it. “The editor said it would be okay in a political cartoon context, but that illustration wasn’t, so better to be safe.” Because of the fear of stepping on the “red line”, all the Five-star flags in his illustrations were replaced with single-star versions.

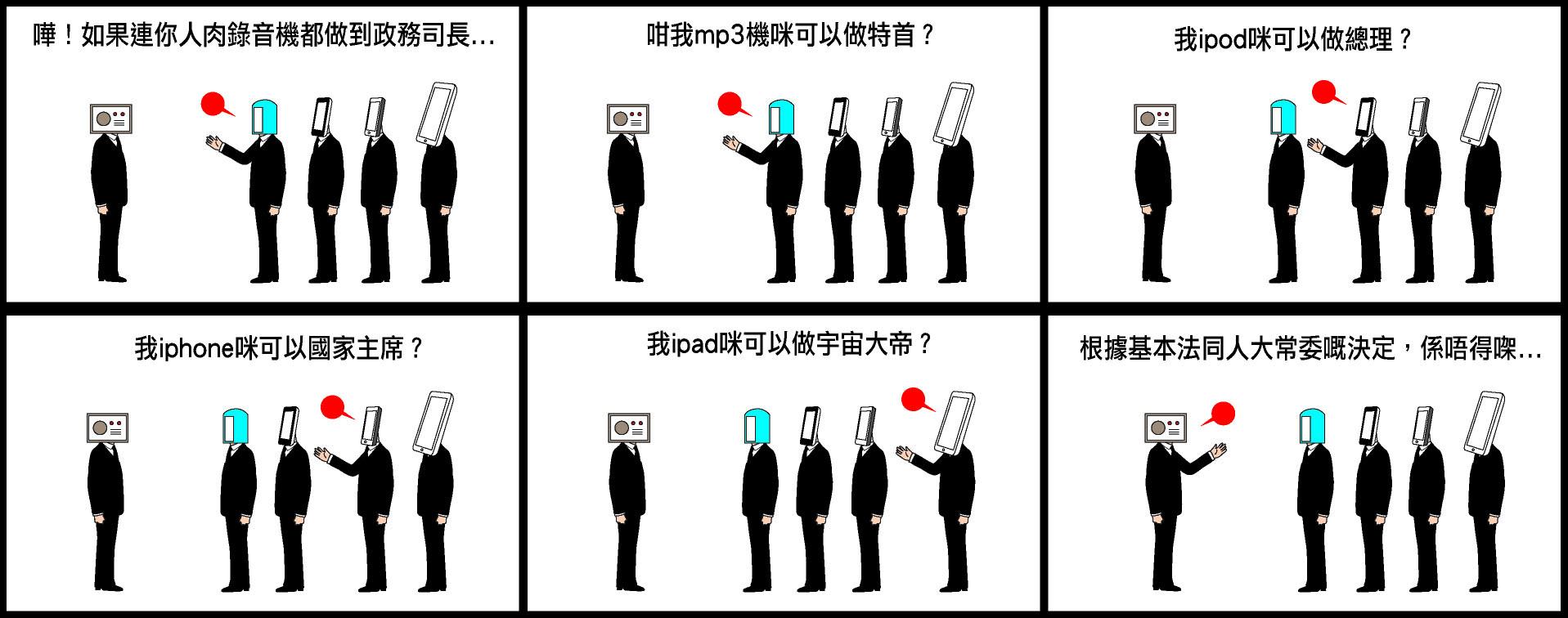

Despite feeling freedom of creation waning, Justin thought he could still manage the red line. Even after the National Security Law came into effect, he wasn’t first overly worried — he shifted his subject matter from the Chief Executive and officials to policies on people’s livelihood. But when his cartoon mocking the Junior Police Call in 2021 led to accusations by the Hong Kong Police, he was stunned. “That cartoon was about the police and the Hong Kong Journalists Association blaming each other, and put it in a school setting, it’s the Junior Police Call and the student reporters. It is always our job to satirise the ills of society with current affairs. In fact, it was a rather mild satire.”

Looking back, he realised the issue may have stemmed from the newly appointed Secretary for Security, Chris Tang. The power of the police has been expanded, and they are more sensitive to their public image following the end of the social movement. Since then, anything involving ‘police’ has become taboo. “I was still quite naïve and thought that if Ming Pao had published it, they would have reviewed it. If I’d known in advance, I wouldn’t have submitted it. Later, I learned that many people at Ming Pao took the heat for me behind the scenes so I could keep my column and continue drawing for the paper.”

Due to his family’s safety and mounting pressure, he decided not to create political cartoons and rebranded his column with a new name, Little Pink Man’s Days, focusing on parent-child themes.

An academic paper reported by the university senior

Even though one of his cartoons had been accused by police, Justin had not considered emigrating—until a short academic paper he wrote in English and published overseas, analysing protest imagery and symbols, was reported to the police by top university management. “I was working on a research project about political cartoons. The article was published in an academic journal in Switzerland and was based on promotional materials I had received during the 2019 anti-extradition protests. It was just a few hundred words. But when the university president saw it, he reported it to the police.”

He said the president at the time, Prof. Alex Wai, had just taken office, and how he handled the case was a clear violation of academic freedom. Justin thought a university should protect its staff. Instead, they reported their own staff for political reasons. “I was shocked. First, the article was not widely circulated. If they had concerns, they could have recalled it or warned me and asked me not to publish similar papers again. But they did none of that before reporting it.”

Feeling that academic freedom had been restricted, Justin resigned from his teaching post and left Hong Kong within four days. “I evaluated that even if I stayed, I had no future. Baptist University would not renew my contract, and none of my funding applications would get approved.” Though he left Hong Kong, losing his status as a teacher for more than a decade left him devastated. He even experienced an identity crisis. Later, he was invited by a UK-based Hong Kong media outlet to resume drawing political cartoons. Though it should have been a joyful return, his feelings were complicated.

Family safety as a constraint for his creations

“Even though my family has moved to the UK, they still travel to Hong Kong. Especially when I’m aware that the national security authority has threatened people close to the wanted exiled activists after issuing a warrant. If I end up on that list, will it affect my family?” Justin admitted that it’s hard to draw political cartoons when constantly thinking about safety. So, even after resuming drawing in the UK, he eventually paused again.

Aside from concerns for his family, his emotional state after leaving Hong Kong has also limited his creativity. “At first, I agreed to resume drawing as a fulfilment of my wish. Since arriving in the UK, I’ve realised that what strikes me most is the sense of ‘losing connection’. I am not in Hong Kong anymore, and I feel disconnected from what’s going on in society. Are the things I draw still relevant? Sadly, it feels like they’re not.” He admitted that compared to Ming Pao, online media has fewer readers, and the lack of feedback left him feeling unmotivated.

Zunzi ends his column – Drawing to keep the candlelight alive

When Ming Pao announced in 2023 that Zunzi’s political cartoon column would be discontinued2, Justin decided to pick up his pen again. For him, it is not just a job, it is a calling. “Even if the candlelight is faint, it must be kept alive—at least a little light remains.” He felt Hong Kong could not afford to lose another political cartoonist. That thought has become his greatest motivation to keep drawing.

Justin admitted that because of his past experiences with censorship in Hong Kong, he still holds back even while in the UK. For example, he uses a ventilation fan as a metaphor for the Bauhinia of the Hong Kong SAR flag. But he continues to draw to satirise figures like Chris Tang. “You know you can’t go back, but you’re not that afraid either. So, I don’t restrict topics, but I am cautious about how far I go.”

Noting the change in publication platforms and audience, Justin has also adjusted his style. “I used to draw in a more subtle style, but now I’m trying to express in a more intense way, hoping to be more direct and powerful.” Previously, he drew six-panel cartoons for Ming Pao, which allowed him to tell a more abstract story. Now, for online media, he draws single-panel works that are more in line with traditional political cartoons. “My style is closer to Zunzi’s now. Since I’ve already left Hong Kong, why not try something different in style?”

Notes:

[1]: Article 23 of Hong Kong’s Basic Law requires the region to enact national security legislation, which triggered widespread public concern. On 1 July 2003, approximately 500,000 people demonstrated against the proposed law, leading to its suspension later that year. However, the legislation was eventually enacted in 2024.

[2]: Hong Kong newspaper suspends satirical comic strip after 40 years, following government complaints, “Cartoonist Wong Kei-kwan, who uses the nom de plume “Zunzi”, has been publishing his satirical takes on current affairs and public policies in the city since 1983 in Ming Pao”

Original Interview in Traditional Chinese:

香港政治漫畫家黃照達:被審查後創作自我設限 堅持執筆冀燭光不滅

曾是香港浸會大學視覺藝術院助理教授的黃照達 (Justin),自2007年開始為《明報》畫政治漫畫,當時的專欄名稱是「嘰嘰格格」,以政治為題材,即使《港區國安法》在2020年生效,他亦沒有停止他的專欄創作。直至2021年9月,他的一則漫畫被香港警方批評是毫無事實根據的指控,詆毀、抹黑少年警訊會員,他才無奈地結束畫了長達14年的專欄。他不諱言,雖然《明報》並無施壓,但在壓力及家人擔憂下只有作出妥協,結束政治漫畫專欄。

事件過後,黃照達一直備受政治壓力,他曾發表一篇僅幾百字的學術文章,分析香港抗爭的圖像與符號,居然有學校高層向警方舉報,成為他極速移民的導火線。即使移民來到英國,他一度感到迷失,基於家人的安全考量,只能不斷在創作過程中自我審查,「當我有是否安全的念頭出現,整個創作就會不一樣。」

2003年七一的政治覺醒

黃照達剛開始跟《明報》的合作,是在校園版畫兒童漫畫,「開始畫政治漫畫是緣於2003年七一的政治覺醒,當時有數十萬香港民眾上街抗議23條立法,發生很多事又參與不了。」他當年仍在英國讀碩士,畢業回到香港後,便為《明報》畫了一篇政治漫畫,「因為我的作畫風格較隱晦,跟傳統政治漫畫不一樣,他們認為很適合報紙風格、很喜歡。」由那時起,他就開始幫《明報》畫政治漫畫,後來更以政治漫畫家的身份為人所知。

「我好像可以將一些對社會的看法或者不滿表達出來,政府亦可以透過政治漫畫了解民意。」黃照達認為,畫政治漫畫最重要的是得到共鳴,即使沒有權力監察政府,也可以將大部分人的想法表達出來。

國安審查前的創作自由

黃照達自2007年正式以政治漫畫家的身份與《明報》合作,他憶述當時的創作風氣相當自由,「曾蔭權當特首那段時間是最無壓力的,當時中國政權對香港的參與度不算高,香港人仍有幻想能夠爭取普選,我又非政治人物,又不懂政治,卻可以參與其中,是最開心亦是創作成長得最快的一段時期。」他續指,大家一直都知道「底線」在哪裡,只要在範圍之內創作就很安全,「如果你是泛民支持者,屬於某個陣營,你會知道對方的界線是甚麼,這純粹是政治生態裏面自己劃分的界線,而非政府限制你說甚麼。」

在黃照達眼中,當時政府沒有意圖限制創作或言論自由,但自己的「底線」是中國新聞,不畫是因為不認識,而非由上而下地被禁止,只要不犯法就可以。很諷刺的是,若現在要把過往的作品拿出來,應該會全部被禁。

由「五星旗」到「一星旗」

黃照達在創作生涯當中首次感受到「紅線」存在,其實早在香港回歸中國《國旗法》和《區旗法》立法之時,「我畫政治漫畫很常用『五星旗』、『區旗』,因為最容易表達中國和香港,《國旗法》通過後,我連『五星旗』都不敢畫,後來由『五粒星』畫了『一粒星』」,他解釋,雖然法例沒有明文規定不可以畫「國旗」,但因為法例列明「不能侮辱國旗」,而大家都不清楚怎樣才算「侮辱」,都是由政權來定義的,「他說我侮辱國旗,我都無法跟他爭辯,惟有自保。」

黃照達又憶述2018年《明報》創刊50周年,他在特刊畫了一篇插圖,當時有畫「國旗」,但被《明報》編輯勸誡避免畫「五星旗」,「他說如果我在政治漫畫的情境下畫是可以的,但現在不是,所以想安全一點」,因為大家都恐懼哪一刻會踩中「紅線」,最後所有作品中的「五星旗」都變了「一星旗」。

雖然感覺到創作自由受限,黃照達認為自己仍然能處理那條「紅線」,即使《國安法》通過後,亦沒有很擔心,只是將題材由特首、官員轉向民生政策,後來2021年的少年警訊漫畫事件,他無法相信自己會被指控,「那篇漫畫的題材是取自警察和記協互相指責,把它放在校園環境內,就是少年警訊和校園記者,以新聞為題材諷刺時弊,一直是我們的工作,而且這篇漫畫挑釁的程度真的很輕微。」事後他再分析事件,因為當時保安局局長鄧炳強剛上任,警權很大,加上社運完結後警察很著意自己的形象,因此不管畫甚麼內容,「警察」都是一個禁忌。

「那時仍很天真,覺得《明報》能刊登,他們應該有審查過,如果我一早意識到會出事,便會停畫。後來我知道,為甚麼『黃照達』這個名字仍然能在《明報》出現,背後有很多人替我承受了很多事情,我才能繼續畫。」黃照達表示,因為家人的安全考量,而自己亦背負了不少壓力,決定結束專欄,不再畫政治漫畫,之後他將專欄易名為「小粉人看日子」,以親子為題材作畫,「突然叫我不畫政治漫畫,好像不懂得畫畫,我畫甚麼好?畫花花草草、山山水水,又好像不是那回事,所以當時有一段時間很迷失,當無機會再畫的時候,覺得事業好像完結了。」他感慨地說。

學術論文被大學高層舉報

黃照達的一篇漫畫雖然被警察批評、指控,但他仍未有移民的想法,直至他發表了一篇以英文書寫、在外國發表的學術文章,分析香港抗爭的圖像和符號,被浸大高層主動報警。「當時我在做一個關於政治漫畫的研究,在瑞士一本學術雜誌上刊登,內容關於我在2019年(「反修例」運動)收到的文宣圖片,於是寫了一篇幾百字的文章去講述其中一些題目,校長見到就決定報警。」

自由的踐踏,大學本應保護員工,當時卻因為政治理由,親手舉報員工,「那一刻我相當震驚,第一就是該論文並未流出市面,如果他認為有問題,可以選擇回收,或者向我發出警告信,讓我不可以再寫,我都覺得仍可以接受,但以上行動他全部沒有做。」

當時,黃照達有感學術自由受到限制,便向任教的大學請辭,更在四天內決定離開香港,「我自己評估,就算我留在香港,都應該沒有前途,浸大一定不會跟續約,而我申請的所有資助都不會獲批。」雖然能夠離開香港,但失去十多年的教師身份令他感到相當失落,更一度陷入身份危機。後來他受到英國港人媒體邀請,重新畫政治漫畫,重拾政治漫畫家的身份本應高興,他卻百感交集。

家人安全成創作的最大考量

「雖然我的家人已移民英國,但他們仍會回港,尤其看到香港政府下通緝令後,國安會威脅身邊的人。如果去到某個位置我被通緝,會否連累家人?」黃照達坦言,畫政治漫畫,如果要思考安全問題,其實很難畫。因此,他在英國重新執筆一段時間後,又再暫停畫政治漫畫。

除了家人的安全考量,離港後的情緒亦限制了他的創作,「起初答應重新執筆,當是圓了自己的心願,但我來到英國之後,有一個字有很大感觸就是『關連性』,因為我不在香港,感受不到社會現象,我所畫的東西是否跟社會有關連?很悲觀地覺得好像沒多大關係。」他坦言跟《明報》相比,網媒的讀者不算很多,好像畫完沒有多大迴響,令他失去繼續創作的動力。

「尊子」停刊 執筆冀燭光不滅

後來《明報》在2023年宣布「尊子漫畫」停刊,令黃照達決定重新再畫政治漫畫,在他眼中,這不僅是一份工作,而是使命,「即使燭光再細微,亦要保持燭光不滅,起碼保存著一絲光。」,他認為香港不能再失去多一位政治漫畫家,成為他繼續畫下去的最大動力。

黃照達直言,因為過往在香港被審查的種種經歷,即使身處英國,作畫時都會「手下留情」,仍會以「抽氣扇」代替「國旗」,但會繼續畫鄧炳強,「你知道回不去,但又不會去到害怕的程度,因此我不會在題材上設限,但會在程度上拿捏得小心一點。」

因為留意到作品發佈的媒介不一樣,受眾不同,黃照達重新創作後在風格上有所調整,「過往的畫風較隱晦,現在開始嘗試較激烈的表達方式,希望直接一點,力量更大。」他解釋,以前在《明報》畫的是六格漫畫,比較抽象,現時幫網媒畫的是一格漫畫,比較接近傳統政治漫畫風格,「現時畫風跟『尊子』比較接近,反正都離開了香港,不如改變一下,嘗試不一樣的風格。」