Brazil: Bill Threatens Human Rights And Climate

The General Environmental Licensing Law (Bill PL 2159/2021), widely referred to as the “Devastation Bill” (Projeto de Lei da Devastação) was approved by the Chamber of Deputies on 17 July 2025, with 267 votes in favor and 115 against, and is now under review by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who holds the power to veto it.

Backed by agribusiness and the oil and gas industries, and approved without adequate public debate or effective participation by civil society, Bill 2159/2021 significantly weakens Brazil’s environmental licensing framework. Among its most alarming provisions is the expansion of the so-called “License by Adhesion and Commitment”, which would allow most projects (excluding only those classified as high-impact) to bypass prior environmental and human rights impact assessments. Under this mechanism, companies could obtain automatic approval based solely on self-declaration, without any evaluation by competent authorities.

The bill also exempts entire sectors, such as agroforestry and livestock farming, from environmental licensing altogether. Projects in these sectors would require only a simple adherence form, with no technical scrutiny of their environmental impacts. Additionally, the bill introduces a “special environmental license” for government-designated “strategic” projects, including oil extraction, enabling them to be fast-tracked through a simplified, single-phase licensing process without full impact assessments.

These provisions against environmental safeguards pose serious risks to the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, recognized by the UN General Assembly, affirmed in the San Salvador Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights (ratified by Brazil), and enshrined in Article 225 of the Brazilian Constitution. The bill also undermines the rights to access information, public participation, and access to justice.

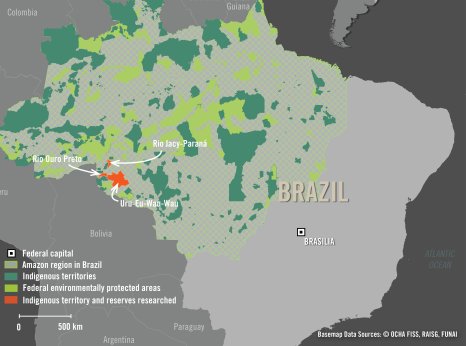

With respect to Indigenous Peoples’ rights, the bill PL 2159/2021 restricts the participation of competent authorities to projects affecting officially demarcated Indigenous lands and titled Quilombola territories, ignoring the reality of land tenure insecurity in Brazil. Around 80% of quilombola territories (TQs) and 32.6% of Indigenous Lands (TIs) are awaiting titling. These provisions severely undermine the rights of indigenous peoples enshrined in instruments ratified by Brazil like the ILO Convention No. 169 or the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

A group of UN Special Rapporteurs has already warned of the grave threats posed by the bill to human, including Indigenous Peoples’, rights. Overall, it represents a major setback to Brazil’s international human rights and environmental commitments. Brazil faces significant human rights challenges, including persistent police violence predominantly affecting Black youth, increasing gender-based violence, and ongoing threats to land and environmental defenders, especially those from Indigenous Peoples and Quilombola communities. Despite some progress, systemic issues like overcrowded prisons, limited social policy investment, and insufficient transitional justice measures for dictatorship-era abuses remain critical concerns.

The surge in deforestation and recurring wildfires, coupled with lax environmental enforcement, intensifies climate risks and undermines Indigenous rights to land and livelihood. The approval of regressive legislation such as the “PL da Devastação” deepens these threats by weakening environmental protections and facilitating exploitation. Brazil must uphold its commitments to human rights, environmental protection, and climate agreements. Not to do so will risk undermining Brazil’s global leadership role in this crucial year for climate action. Effective responses depend on strengthening democratic oversight, ensuring justice for marginalized groups, and restoring robust environmental governance.