Press releases

Somalia: UK's 'failed' refugee policy highlighted as thousands forced to return from Dadaab camp

70,000 Somali refugees have been pressured to return from Kenya since 2014 and now face a country devastated by conflict and drought

2.1 million are internally displaced in Somalia and thousands have been killed by fighting and a cholera outbreak

‘The dire situation faced by Somali refugees in Kenya is yet another reminder of why Theresa May’s approach to refugee protection will continue to fail’ - Steve Valdez-Symonds

Thousands of Somali refugees who were pressured into leaving the Dadaab camp in Kenya are now facing drought, starvation and renewed displacement in Somalia, Amnesty International said in a new report today (21 December).

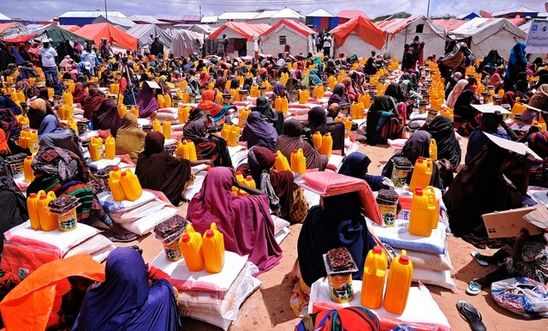

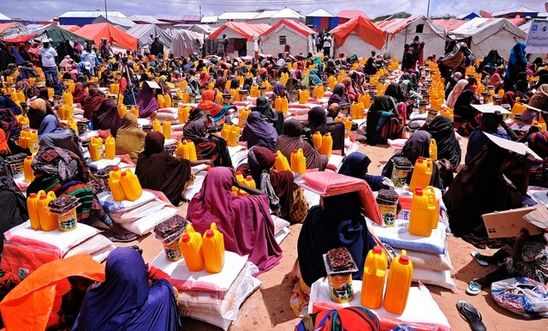

Between December 2014 and September 2017, the UN has facilitated the return of more than 70,000 Somali refugees from Kenya. Returns from Dadaab, which currently houses nearly 240,000 people, have massively accelerated since May 2016, when the Kenyan government announced plans to close the camp. Huge levels of returns have continued even after the Kenyan High Court ruled the camp closure was illegal in February 2017.

In a new report, Not Time to Go Home, Amnesty researchers interviewed returnees living in dire conditions in overcrowded cities or displacement camps in Somalia. Many returnees said they had left Dadaab because of diminishing food rations and services, or because of fears stoked by Kenyan government officials that they would be forced back with no assistance. They now face life in a country blighted by decades of conflict which is also experiencing a devastating drought and a deadly cholera outbreak.

UK’s ‘failed’ response

The situation for Somali refugees highlights the failings of the UK Government’s policy towards international protection of refugees, which emphasises that people fleeing conflict and persecution should seek support and remain in the ‘first safe country’ they reach. This leaves most of the responsibility with countries that border conflict zones, which are often too poor or too unstable themselves to provide support to all who need it.

Steve Valdez-Symonds, Amnesty UK’s Programme Director for Refugee and Migrant Rights, said:

“The dire situation faced by Somali refugees in Kenya is yet another reminder of why Theresa May’s approach to refugee protection will continue to fail.

“The UK Government keeps pretending that the best way to support the millions around the world who have been forced from their homes by conflict or persecution is to help them stay in the so-called ‘first safe countries’ they reach. But this is clearly just a policy of leaving other – often much poorer and less stable – countries with nearly all the responsibility for hosting displaced people.

“For years this has left countries like Kenya hosting refugee populations, putting the UK and other wealthy countries to shame. Even the financial assistance offered by the international community to support host countries has been far below the bare minimum needed.

“The results have been entirely predictable - countries neighbouring conflict and crisis have steadily lost the will or capacity to provide asylum, while the women, men and children who have fled desperate situations are the ones who suffer, being left without any safe options.

“This pattern is something the UK and richer countries can no longer ignore – they need to do much more to share the responsibility in hosting and assisting refugees.”

Pressure from Kenya

In November 2016 Amnesty documented Kenyan government officials threatening refugees and telling them they had to leave, raising serious questions about whether returns were voluntary.

Charmain Mohamed, Amnesty International’s Head of Refugee and Migrants Rights, said:

“In its zeal to return refugees the Kenyan government has made much of small security improvements in Somalia, but the grim reality is that many parts of the country are still plagued by violence and poverty.

“Refugees who fled drought, conflict and hunger in Somalia were coerced into returning in the midst of a severe humanitarian crisis, and many now find themselves back in the same hopeless situation from which they fled and still unable to go home.

“Until there is a significant improvement in humanitarian conditions, the Kenyan government must focus on providing continued protection to Somali refugees.”

Humanitarian crisis in Somalia

Somalia has been blighted by conflict for decades. Between January 2016 and October 2017 there were about 4,585 civilian casualties. The armed group Al-Shabaab, in the last year alone, have carried out indiscriminate attacks which have killed or injured hundreds of civilians.

Meanwhile, the humanitarian situation in Somalia continues to deteriorate. The country is currently experiencing a devastating drought and there is a persistent threat of famine. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) more than half the population is in need of humanitarian assistance.

This combination of factors has led to a huge internal-displacement crisis. As of last month, there were 2.1 million internally-displaced persons (IDPs) in Somalia, many of whom have crowded into urban areas, placing a huge strain on resources. The lack of clean water in Somalia has also triggered a cholera outbreak which killed at least 1,155 people between January and July this year.

Life without water or shelter

Somalia is clearly not ready for the large-scale returns that have accelerated since 2016. Nearly all the returnees interviewed by Amnesty stated that they and their families were facing serious hardship in Somalia.

Amina, a woman in her thirties, fled to Dadaab in 2011 because of drought. She was repatriated to the Somalian city of Baidoa with her husband and seven children in August 2016. She told Amnesty that the water available in Baidoa is both unsafe and prohibitively expensive: “The biggest problem that we have in the area is water. We buy a jerry-can of dirty water for 7,000 shillings [UK£9]. We can go for some days without water.”

Because many returnees cannot return to their original homes, shelter is also a major problem. Nearly all the returnees interviewed by Amnesty said that they had been unable to secure adequate shelter, and many were living in or around IDP settlements. Somalia is also experiencing serious food insecurity and most returnees rely on assistance packages and humanitarian aid for food.

Igal, 40, also went to Baidoa after leaving Dadaab with his six children. He told Amnesty: “If you visit our homes you will see people who have eaten nothing for at least three days.”

An international failure

A key factor behind the Kenyan government’s push to return Somalis is a lack of adequate support from the international community. Funding for the refugee response in Kenya has declined sharply since 2011, far outpacing the reduction in refugee numbers.

Last month, the UN refugee agency’s (UNHCR) appeal for its refugee response in Kenya was only 29% funded. In the same period, the World Food Programme also experienced regular and chronic underfunding, forcing it to repeatedly reduce the value of the food rations given to refugees.

Amnesty is calling on the international community to provide adequate technical and financial assistance to the government of Kenya, to support sustainable and long-term solutions for the integration of refugees in the country. This should include fully funding UNHCR’s appeal for the Kenya response, as well as increasing resettlement places and alternative pathways for Somali refugees.