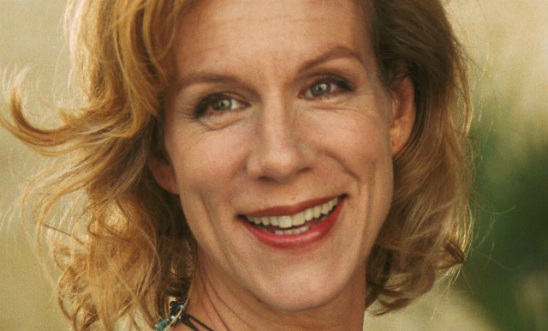

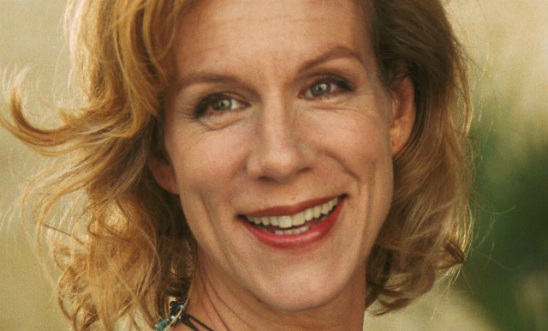

Interview

Juliet Stevenson talks to Amnesty Magazine

Actress Juliet Stevenson spoke to Amnesty Magazine about helping refugee children, playing Paulina, a Chilean detained under the Pinochet regime – and why as a chold she felt she didn't really belong.

Want great content like this delivered to your door? Join Amnesty now

Describe your childhood

It was peripatetic because my father was an Army officer and was posted to a new place every two years. I lived in Germany, Australia, Malta. I have no roots. I often felt like I didn’t belong but learned to adapt fast.

When did you first experience injustice?

I was six and living in Malta. I clearly remember being driven through poor, slum housing looking for our lost dog. It was nothing like where we lived. I was shocked by the poverty and unfairness. My mum said I started drawing long rows of little terraced houses with me living right in the middle, the same as everybody else.

What’s special about your choice of poem for our new anthology Poems That Make Grown Women Cry?

I chose the poem The Kaleidoscope – it’s part of a beautiful collection Douglas Dunn wrote for his wife after she died of cancer. It is exquisite and achieves what I love: the quiet, potent distillation of a moment of intense loss. It’s deeply moving.

Was a love of poetry the start of you being an actress?

Absolutely. When I was nine, I read a poem by WH Auden and had an overwhelming desire to communicate it to an audience. It hit me like a thunderbolt. My drama teacher – encouraging and challenging – also saw something in me. I was quite shy with a lisp and had no confidence with the way that I looked. She gave me a sense that acting might be possible.

You’ve recently spent time in the refugee camp in Calais…

I've been a lot over the past six months. The conditions there fired me to become active. I’m involved in Citizens UK’s project to bring unaccompanied children in the camp to the UK. They have legal rights to this because they have family here but the Home Office isn’t processing their claims. I also bought a double-decker bus on e-Bay and had it converted to use as a women and children’s centre, as the police smashed up their old one. It was surprisingly easy to do. I had asked one of the volunteers what was needed. It was a week before the evictions; everyone was frightened. She said 'I dream of a double decker bus that's warm, dry and we can drive it away with the children if we have to'. We drove the bus into camp in March.

What's your latest project there?

I’m working with my husband and stepson Tomo on a documentary called #HumansAfterAll. For months Tomo has been in Calais filming refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Sudan, Iraq, all over the world. He started as a volunteer in the kitchen and gradually got to know people. The stories are incredible. He filmed only their hands to protect identities -but what started as an expedient measure has emerged as a moving, eloquent feature.

Are human rights and acting connected?

There’s a strong link – imagining yourself into somebody else’s life, trying to understand others with very different lives without judging. I first encountered the refugee community when playing Paulina in Death and the Maiden.

You won the Actress of the Year Olivier Award for this play in 1992. How did it inspire your work on refugees?

Paulina was detained, raped and tortured under the Pinochet regime. Years later, her husband brings home a stranger and she instantly believes his voice to be that of her torturer – she was blindfolded so never saw faces. She takes him captive in her living room and interrogates him. For the first time as an actress, I felt I couldn’t play this part without help. I went to the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture, under Helen Bamber, and she introduced me to Chilean refugees who talked of torture and detention with extraordinary openness and generosity. I got involved. I couldn’t walk away from the people or the foundation.

What other role of yours has been hard to play?

Mother Teresa (The Letters, 2014) was a big leap because I’m not a Christian. We filmed in India, where she’s still a heroine. Being there helped me to understand her. She was in a religious order that wasn’t allowed out beyond a wall, but she kept peering over it, at the poverty and discrimination. She had to walk into the difficulty and be part of it. Whatever else you think of her, that’s admirable.

What makes you angry?

The blind and brutal negligence of refugees by our government and other European governments who squabble about ratios, number crunch and argue while failing to respond to this refugee catastrophe. Our government is turning its back on the unimaginable hardship these refugees face. This moment in history requires compassion and political wisdom.

What makes you happy?

Being with my family, walking, the seaside, being under the sky.

What’s your biggest achievement?

Being with my husband for 23 years. I love Hugh just as much if not more than I did.

Who inspires you?

My mother. She’s fantastic, a progressive thinker. And the late Helen Bamber, founder of the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture, who became my friend and mentor.

If you could change one thing in the world?

I’d let women have a go at running it. They might be better suited to collaborative decision making!

What does Amnesty mean to you?

Amnesty was one of the first NGOs I heard of in my teens – it’s always been a light, so I feel proud of any connection with it. How it has sustained its integrity as a trusted and vigilant voice for human rights over the years is amazing.

Juliet is a contributor to our anthology Poems That Make Grown Women Cry – buy it now for the special price of 13.99.

See Juliet’s work in Calais at helprefugees.org.uk and watch interviews from there filmed by her stepson Tomo at onourradar.org/calais

This is an edited version of an interview first published in Amnesty Magazine Summer issue 2016.