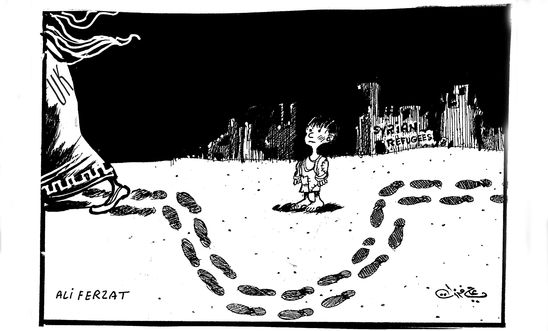

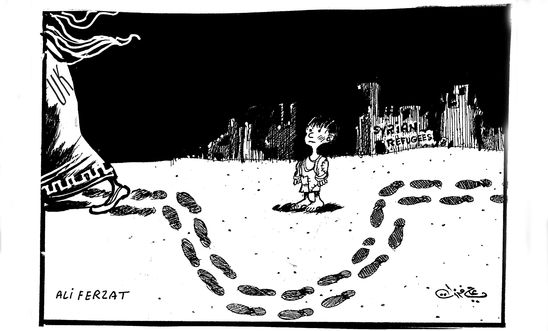

Syrian refugee crisis by cartoonist Ali Ferzat

We’ve commissioned a powerful new cartoon from Ali Ferzat, one of the Middle East's most famous political cartoonists, in collaboration with Mosaic Syria.

The cartoon shines a spotlight on the UK’s pitiful response to take in more Syrian refugees – just 90 people have been resettled. We’ve been calling on the UK government to significantly increase this number.

As the uprisings of the Arab Spring spread, protestors in Syria's cities held up Ali’s sharp, satirical drawings lampooning the authorities as symbols of freedom.

Our Press Officer Naomi Westland interviewed Ali back in 2012 – one year into Syria’s bloody conflict.

When she met him, Ali was still recovering from a brutal attack in Damascus by masked men who broke his hands and fingers in an attempt to stop him from drawing again. All the bones in Ali’s hands were broken by the men he refers to as ‘President Assad’s thugs’.

This is Ali’s blow-by-blow account of the events leading up to the assault that left him unable to hold a pen properly for months.

An enemy of the regime

Ali Ferzat had met Bashar al Assad a number of times during his career and exchanged friendly words. Ferzat said Assad – whose father was in power at the time – visited his exhibitions where they would discuss the realities of life for the ordinary people depicted in his drawings.

All that changed in 2001, when the artist launched a new satirical magazine called Al Domari.

Bashar al Assad had taken over as president from his father the previous year promising democracy, openness and transparency. They were empty promises, said Ferzat.

After a brief period of openness in the early 2000s, the regime started to clamp down on dissent. Al Domari became the ‘enemy of the regime and lots of business people hated it’ for the fun it poked at the corrupt and nepotistic Syrian political system.

Until that point Ferzat, like other Syrian satirists, had avoided overt criticism of the government in his work.

‘You couldn’t target the president or those around him with jokes or drawings. Criticism had to be more symbolic and subtle. You could criticise the president, as long as it was the president of Nicaragua.’

Ali Ferzat, interview with Naomi Westland in 2012

When he launched his magazine the government hadn’t expected it to touch on taboo issues, criticising the intelligence agency or the parliament.

But while Ferzat refrained from direct criticism of the president himself, the overt targeting of the authorities struck such a chord in Syria that Al Domari, published twice daily, was a sell-out.

It didn’t take long for the regime to catch up with him and in 2003 they shut down the magazine.

Not to be deterred, Ferzat turned to the internet, which he calls the ‘new tool for modern revolutions’ after the role it has played in uprisings and popular resistance across the Middle East.

That’s when the trouble really started.

‘People started visiting my website, not only people in Syria but from all over world. More and more people were seeing my work,’ he said.

What they got was a glimpse of the political realities facing the Syrian people as the regime cracked down on opposition. Ferzat decided the president had gone too far in stifling freedom of speech and crushing dissent.

The time had come for him to take a more direct approach in his work.

The last taboo

‘I decided to break the last taboo – criticism of the president himself. It was three months before the uprising started. And suddenly everyone, in the coffee shops and in their homes, was talking about it. It opened the way for people to start criticising Assad.’

Ali Ferzat

Ali was delighted that protestors on the streets held up his drawings – one shows Assad trying to hitch a lift with an outgoing Gaddafi, another shows the president reluctantly tearing off the page of a calendar on a Thursday, knowing that the following day would bring more protests.

But unsurprisingly, not everyone was pleased and Ferzat started to receive threatening calls and messages.

At first he didn’t pay much attention, until the early hours of 25 August 2011, when he left his office at 5am to make the 10km drive home.

‘I was heading towards Al Mouwayeen square. It is the most secure place in the whole city because it is right between the presidential palace, the intelligence services headquarters, the state TV broadcaster and army barracks. If you so much as light a cigarette in the square you’ll have 20 police cars immediately surrounding you.’

‘I was driving and a white car was driving right behind me even though the streets were empty. It hit me from behind and pushed my car off the road. Three men, all well-built and with their faces covered, got out of the car. It had blacked out windows – like the official intelligence service cars.’

‘They beat me with batons for about 15 minutes while I was still inside the car. They put a bag over my head and beat me all over my body. I heard one of them say: break all his fingers so he can never draw and criticise the president again.’

The price of free speech

The men dragged Ali from his car, put him in the back seat of theirs and drove off, eventually dumping him on a roadside heading out of Damascus.

He lay there unconscious for what he said was a few minutes. When he came round he crossed the street to try and hitch a lift back into Damascus but no one would stop.

‘I looked very scary. My face was double its normal size, swollen from the beating. I couldn’t see out of my right eye. I was bleeding from my head and my hands.’

Ali Ferzat

Finally, a passing truck picked him up and dropped him home, travelling on back streets so as not to be noticed by the police.

‘I didn’t knock on my own door because I didn’t want to scare my family, I must have looked so terrible,’ he said. Instead he roused the night-watchman who took him to a nearby hospital.

‘So that was the price of freedom, of practicing freedom of speech,’ he said.

For the first month after the attack he received 200-300 visitors, people brought flowers and lit candles outside his house. But he had to leave to get proper medical treatment for his hands, which he still couldn’t use properly. He couldn’t control a pen easily and struggled to grip.

He got a call from the owner of the Al Watan newspaper in Kuwait and he insisted Ferzat go to Kuwait to be treated. Despite fears that he would encounter problems leaving the country, he sailed through security with no questions asked.

‘Maybe it helped that on the day of the attack everyone was talking about it, even the White House condemned it,’ he said. ‘Maybe that recognition meant they left me alone.’

‘Humanity will take its revenge’

At the time of this interview, Ali's hands were ‘95 per cent’ better and he could draw again. He hadn’t been back to Syria since he left in the previous autumn, but he didn’t consider himself an exile.

‘I feel very bad about what is happening in Syria, and the people on the streets, sacrificing everything, they are better people than me.’

‘We have witnessed tsunamis,’ he said. ‘When you violate human rights and attack humanity, humanity will take its revenge and create its own tsunami. I think the regime is at the end of the road, but the revolution is only just beginning.’

These were Ali’s words three years ago.

Since then the conflict in Syria has morphed into what has been referred to as the worst humanitarian catastrophe of our time.

Ten million people have been forced to flee their homes. Four million of them are living in precarious, often dangerous, conditions in neighbouring countries.

The conflict not only shows no sign of abating but it has entered new and ever more deadly dimensions.

'The West stood looking at the biggest tragedy in the world and…they used the policies of the three Monkeys: I do not see, I do not hear and I do not talk.'

Ali Ferzat, interview with The Independent in 2015