Press releases

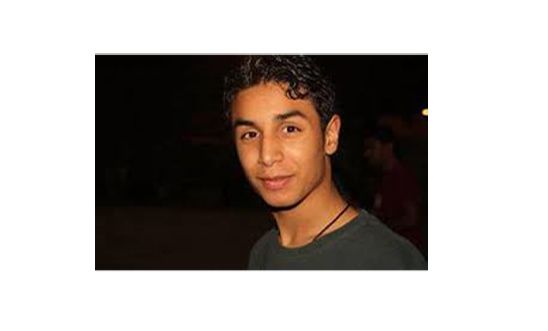

Saudi Arabia: King Salman should refuse to ratify Ali Mohammed al-Nimr's death sentence

At least 134 people executed in Saudi Arabia so far this year

‘We’d like to see the UK government speaking out publicly about Ali al-Nimr’s case’ - Allan Hogarth

King Salman of Saudi Arabia must refuse to ratify a death sentence against the child offender Ali Mohammed Baqir al-Nimr, Amnesty International said today.

Amnesty is calling on the authorities to quash Ali al-Nimr’s death sentence, which has come after a grossly unfair trial and was based on “confessions” Ali al-Nimr says were extracted under torture.

Ali al-Nimr was sentenced to death by a Specialised Criminal Court, a security and counter-terrorism court, on 27 May last year, and with the sentence already upheld by an appeals court and the country’s Supreme Court - without his or his lawyer’s knowledge - he could be executed as soon as King Salman ratifies the sentence.

Ali al-Nimr was sentenced to death by the Specialised Criminal Court in Jeddah for a list of 12 offences that included taking part in demonstrations against the government, attacking the security forces, possessing a machine-gun and carrying out an armed robbery. The court seems to have based its decision solely on “confessions” which Ali al-Nimr has said were extracted under torture.

Saudi Arabian officials have not yet responded to international criticism on Ali al-Nimr’s case, though officials have in the past vehemently denied using the death sentence against child offenders.

Amnesty International UK’s Head of Policy and Government Affairs Allan Hogarth said:

“Saudi Arabia’s human rights record is already in tatters, but King Salman could at least prevent further damage by refusing to ratify the outrageous death sentence against Ali al-Nimr.“For its part, we’d like to see the UK government speaking out publicly about Ali al-Nimr’s case and making urgent representations to the authorities in Riyadh about his plight.“After the UK was too quiet for too long over the blogger Raif Badawi’s shocking sentence, we hope that ministers will have learnt the lesson that they need to speak out early and forcefully on cases like Ali al-Nimr’s.”

Child offender

Ali al-Nimr was arrested on 14 February 2012, when he was only 17 years old. The security forces did not produce an arrest warrant on detaining him. He was taken to the General Directorate of Investigations prison in Dammam, in the Eastern Province, where he says he was tortured to “confess” and deceived into signing written statements that he was not allowed to read and was misled into believing were his release orders. He was not allowed to see his lawyer or his family. He was then taken to a centre for juvenile rehabilitation, Dar al-Mulahaza, where he was held until he was returned to the prison in Dammam when he had become 18. This apparently indicates that the authorities recognised and treated him as a child offender when they first detained him.

Violations of international and Saudi Arabian laws

In sentencing a child offender to death, Saudi Arabia has violated its obligations under international customary law and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which it is a state party. Article 37(a) of the Convention provides that “Neither capital punishment nor life imprisonment without possibility of release shall be imposed for offences committed by persons below eighteen years of age.”

In addition, the Saudi Arabian authorities have in Ali al-Nimr’s case violated both international law and standards on fair trial rights during appeals, as well as the right to appeal provided by Saudi Arabian law. Under Saudi Arabian law, convicted individuals can appeal a first-instance court decision in writing within 30 days of the sentence, but because Ali al-Nimr was prevented from meeting his lawyer, he was not able to present any appeal. According to international law and standards, fair trial rights must be respected during appeals, including the right to legal counsel, the right to adequate time and facilities to prepare the appeal, the right to equality of arms and the right to a public and reasoned judgment within a reasonable time.

The Saudi Arabian Law of Criminal Procedures, specifically Articles 36(1) and 102, other national law, as well as international treaties to which the country is a state party, particularly the Convention against Torture, clearly and categorically prohibit the use of torture or other ill-treatment. However, in Saudi Arabia defendants are routinely subjected to such practices to force them to “confess” to committing crimes. They are often, as it appears in Ali al-Nimr’s case, convicted solely on the basis of signed “confessions” obtained under torture or other ill-treatment, duress or deception, that are admitted by judges as evidence in trials.

Eastern Province unrest

Ali al-Nimr is one of at least seven Shi’a Muslim activists who were sentenced to death in 2014 following protests that have taken place in the country’s Eastern Province since 2011. At least 20 people suspected of taking part in those protests have been killed by security forces since 2011, and hundreds have been imprisoned, including prominent Saudi Arabia Shi’a Muslim clerics. Ali al-Nimr’s uncle, Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr, a prominent Shi’a cleric and the Imam of al-Awamiyya mosque in eastern Saudi Arabia, is one of those sentenced to death in relation to Eastern Province protests. He was detained without an arrest warrant on 8 July 2012 and sentenced to death by the SCC on 15 October 2014 after a deeply-flawed trial and for vaguely-worded offences that violate the principle of legality. Some of the offences which he is accused of committing are not recognisably criminal offences under international human rights law.

Prolific use of death penalty

Saudi Arabia is one of the most prolific executioners in the world. So far this year it has executed at least 134 people, almost half of them for offences that do not meet the threshold of “most serious crimes” for which the death penalty can be imposed under international law. Most of these crimes, such as drug-related offences, are not mandatorily punishable by death, according to the authorities’ interpretation of Islamic Sharia law, meaning that judges are expected to use their discretion to apply the death sentence in these cases. The death penalty is also used disproportionately against foreign nationals, the majority of whom are migrant workers with no knowledge of Arabic - the language in which they are questioned while in detention and in which trial proceedings are carried out. They are often denied adequate interpretation assistance. Their country’s embassies and consulates are not promptly informed of their arrest, or even of their executions. In some cases families of migrant workers as well as families of Saudi Arabian convicts are neither notified in advance of the execution nor are their bodies returned to them to be buried.